Song Story: "Bay of Suvla"

Plus another early demo for paid subscribers

While writing Foreign Skies, I knew that there was at least one goal I wanted to accomplish. I had actually encountered a couple of historical, Great War-themed albums before but had noticed that most of them focused heavily or exclusively on suffering and death. But actually reading war diaries, poetry, and various accounts it seemed to me that the actual experience of the First World War was not being fully captured.

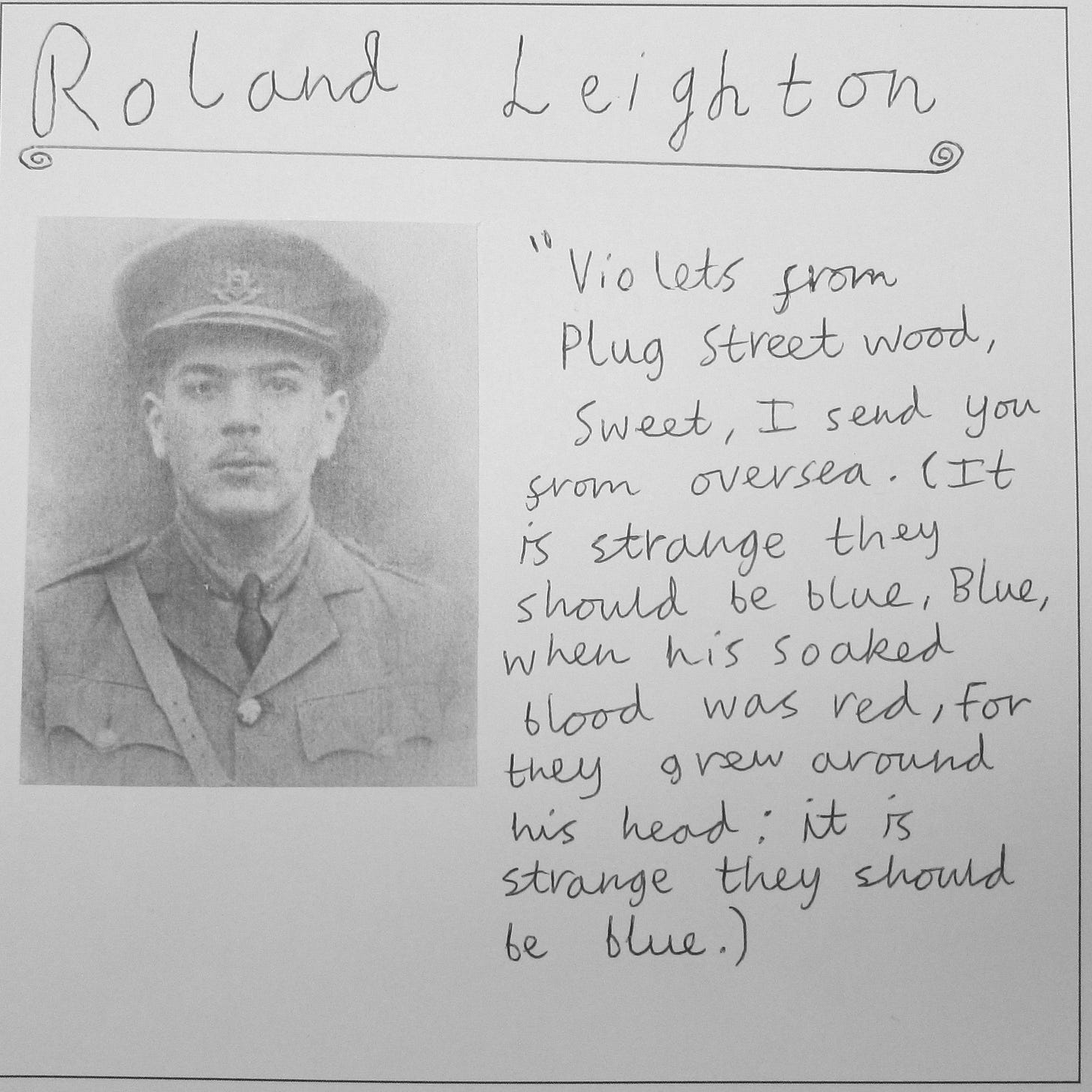

One uncomfortable experience that many soldiers reported was the longing to return to the trenches while on leave. This is memorably captured in Vera Brittain’s stunning wartime memoir, Testament of Youth (the film is amazing if not exactly uplifting or cheery). Roland Leighton, Vera’s young lover, returns from the fighting for a couple of weeks and is strangely distant and absent. Near the end of his leave he breaks down and reveals that he is posessed by a desire to get back to the fight.

It’s not, as warmongering reactionaries will have you believe, that men secretly love fighting and killing and that war gives them the chance to do this. Real accounts of life in the trenches do not reveal much killing at all—after all, this was a conflict in which 65% the casualties were from long-range shelling, and in which most others were from things like indiscriminately sprayed machine-gun bullets. This was not a time to satisfy one’s supposed masculine lust for enemy blood.

But what Roland (and many others) desperately did miss, particularly in the early years of the war, was the sense of purpose, the camraderie, the feeling of being caught up in something that desperately mattered. As the years wore on, this powerful feeling was to give way to cynicism and nihilism, but in 1914 and 1915 it was an absolutely dominant part of the war experience for most soldiers (and, as Brittain’s own account makes clear, for many heroic war nurses).

But the song… well of course I had to have a song about the battle of Gallipoli, one of the most famous blundering disasters in military history. And when I shared a demo of Bay of Suvla to someone to ask for opinions, they bluntly asked whether it wasn’t a bit cheery. And so I returned to my sources to check, and there it was, plain as day; account after account of people being both devastated by the war and also, strangely, missing it. This, I think, is because of those organic experiences of togetherness and shared purpose which can completely disappear in the modern, atomized, efficient, endlessly managed world. I.e. the sort of experience I wanted to capture in Bay of Suvla, even if it did make for a “cheery” song. The reality is that the soldiers on their way to Suvla were cheery; they believed they were going to end the war, they believed they were going to rout the enemy and “string up the Kaiser”.

Anyway, a final thing about this song: aside from it actually sounding eerily like “The Times, They Are A’Changin’”, we were in rehearsal and the line “Care thee well my pretty young maids” just sounded so cliche, hokey and almost, well, offensive, that we kept trying to switch it to something else. We tried a million lines, but the one we kept thinking to use was “Fare the well my Liverpool maids”, which not only doesn’t make historical sense (none of the ships sailed from Liverpool) but which is jusme.

But the remember Seamus saying: “OK, but what would those guys have actually said, and what works with the rhythm of the song?” And we realized that “Pretty young maids” was the right line. But not before knocking out this demo, which was the first time we maid it all the way through the song, and which contains that terrible, silly “Liverpool” line. The best thing about this demo is that my brain fiercely wants to sing the real lyric but I keep trying to force myself back into the more “appropriate” one. Lawl.

Paid subscribers, enjoy…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Roll And Go: Dreadnoughts Blog to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.